If you’re like me and you live on the Gulf Coast, you probably think Gulf oysters are in great shape. In New Orleans they are cheap, and they are everywhere. There are dozens of restaurants that serve Gulf oysters for a dollar or as little as a quarter at happy hour.

We’re blessed with such abundance that we can serve entire dishes made from oysters. Items like an oyster po’ boy would be an unimaginable luxury if you used West Coast oysters that typically cost $3.00 or more a piece. Without the affordable prices that come with abundance, many of our favorite foods would become luxury items available only to the wealthy.

But how much longer will the age of cheap oysters continue if we don’t care for our natural reefs?

I’ll admit that when I attended the annual meeting of the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission meeting earlier this year, I had no idea that oyster production had been declining in the Gulf since the mid-2000s. State representatives from Florida, Alabama and Mississippi all painted a grim picture.

“Oysters are in trouble, and we have no idea how to help them,” was the message I took away from the Eastern Gulf presentations. Florida, Alabama and Mississippi have been using money from the BP drilling disaster settlement and other funds to restore their natural reefs, but little has been working.

In Florida, young oysters are not surviving into adulthood. Ditto with Alabama. I believe the phrase “throwing good money after bad” might have been used. Low oxygen, a lack of freshwater flowing from waters that passed through Georgia, and acidification are all suspected, but no scientific consensus has emerged yet.

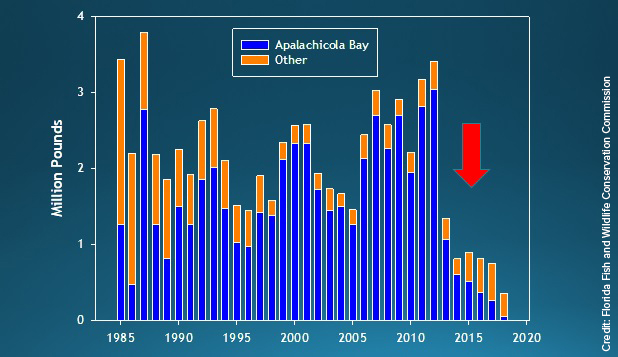

Florida oyster landings:

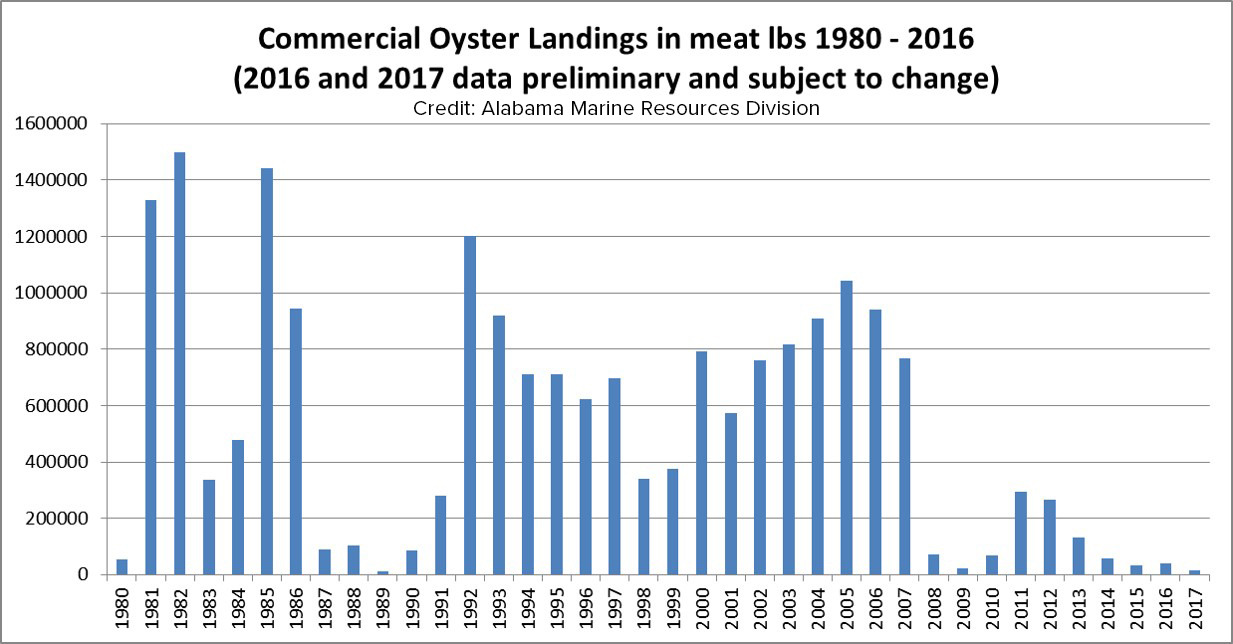

Alabama oyster landings:

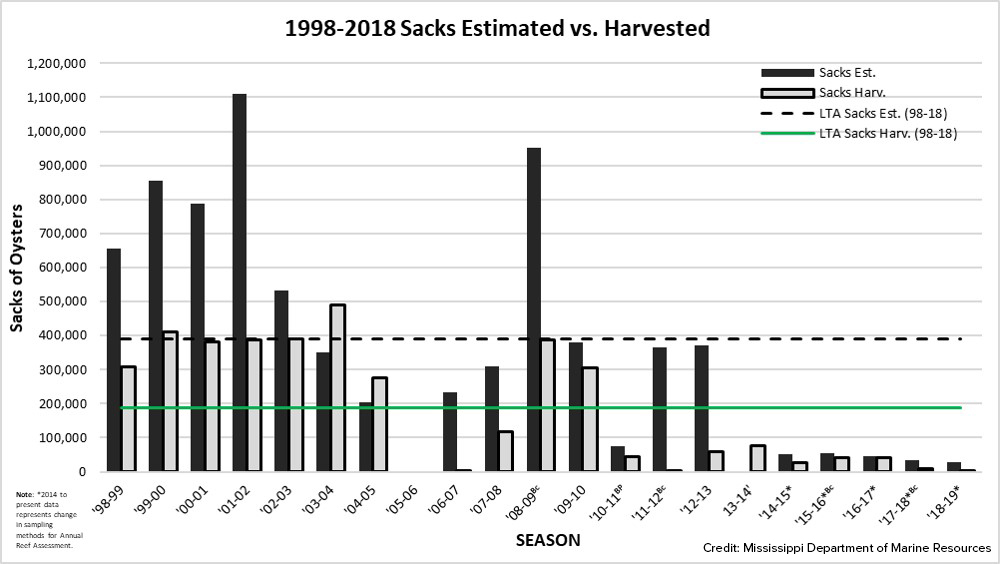

In Mississippi, oysters were in big trouble even before the opening of the Bonnet Carre spillway delivered a crushing amount of freshwater to the beleaguered oyster fishery. We may not have any Mississippi oysters at all this year. Oysters need a healthy mix of salt and freshwater and prolonged changes in either direction can be lethal because they have no way of moving out of the path of freshwater.

Mississippi oyster landings:

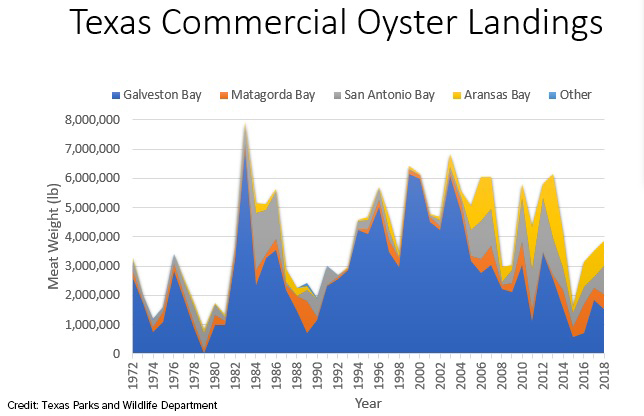

Texas presented a more complicated situation. Oyster production plummeted in 2015 but has rebounded in the last couple years. Still, the overall trend since the early 2000s is still one of decline. Officials in Texas are definitely concerned about the future of their fishery.

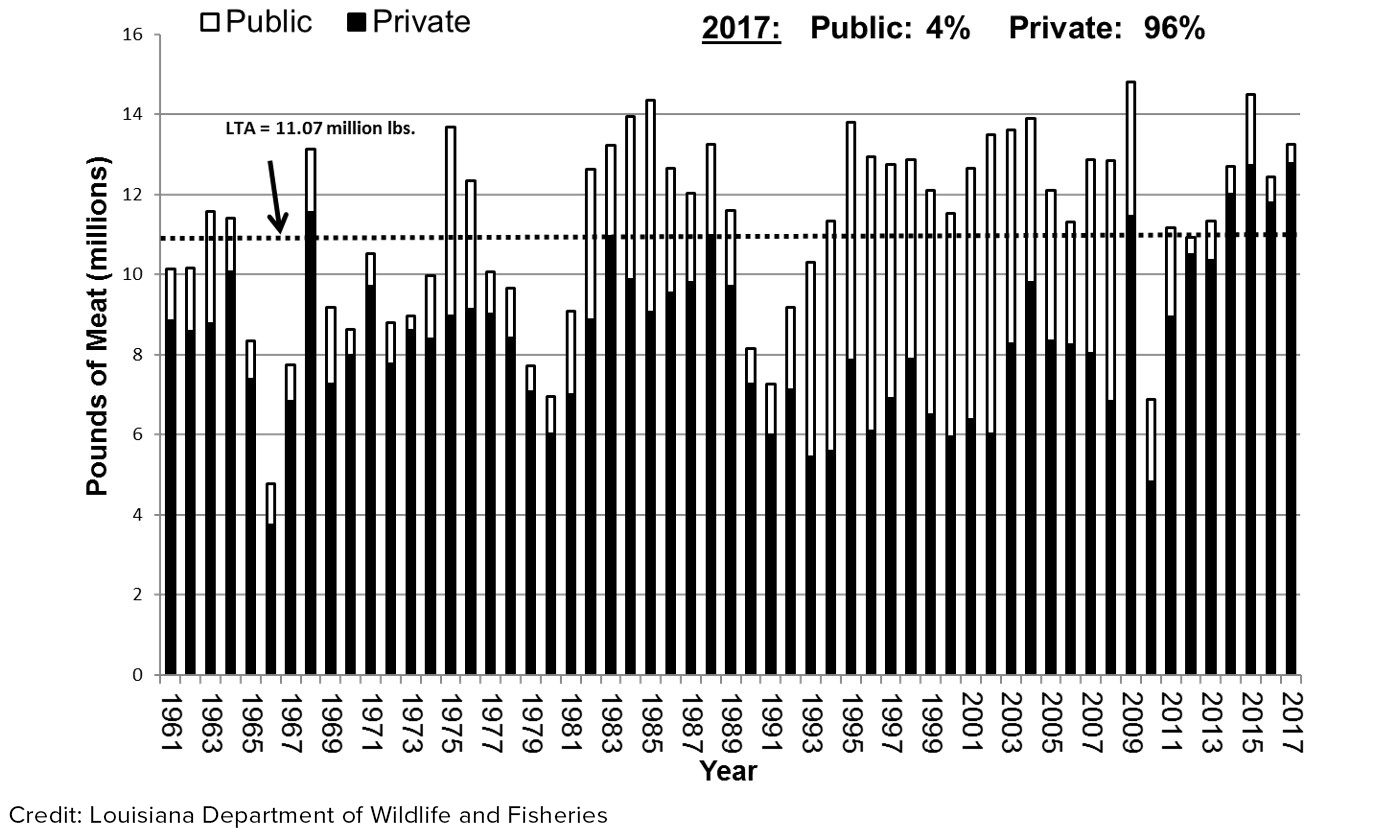

Louisiana is the one exception. While the public oyster reefs continue to decline in accordance with what the other Gulf states have been experiencing, private leases are doing well. Private leases are natural oyster reefs but the access to the reef is limited to a single individual or company. That individual or company is responsible for maintaining the reef with its structural material called “cultch” (limestone, old oyster shells, concrete, etc.) and baby oysters called “spats.”

The situation is complicated by the fact that most of the spats and some of the cultch are taken from the public oyster reefs. The public reefs act as a commonly owned bank that everyone is allowed to withdraw from once per year.

I asked the Louisiana officials why their reefs were doing well when others were collapsing. Could it be that land loss and saltwater was somehow creating more suitable oyster habitat from what used to be freshwater marshes? “No” was the answer from Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries. They believed that Louisiana’s success comes from the private model. If other states turned their public reefs over to the private sector, they said, better management would result.

I’m not sure I buy that argument. Louisiana has always had mostly private leases, and that did nothing to prevent large drops in oyster production in the late ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s from hurricanes and freshwater events. But if private management is the answer, couldn’t we just mandate those best practices with state laws and keep oyster grounds open to the public?

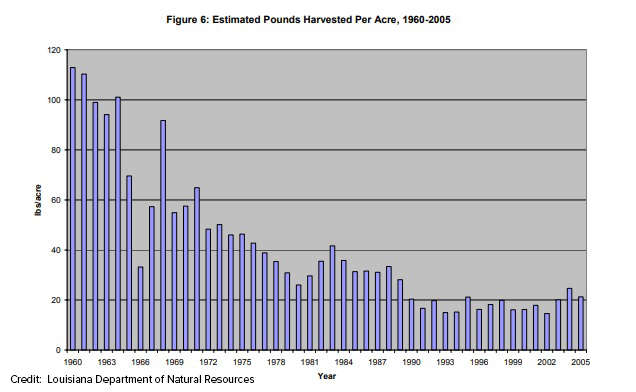

Louisiana’s data is also based on total pounds of meat harvested. But a study from 2006 shows it’s more complicated than that. The study looked at pounds per acre harvested and showed a consistent decline in oyster production going back to the 1960s. We need an updated chart based on pounds per acre to really see if the increased production has come from simply increasing our oyster harvesting effort.

Because oysters are incapable of moving and rely on water quality for their abundance, they represent the canary in the coal mine in terms of Gulf water quality. What the states’ data shows is that all of our fisheries could be headed for big trouble. Drastic changes in salinity, hypoxia and red tide from nutrient pollution, and industrial/plastic pollution in our waterways will continue to devastate our fisheries if we don’t clean up our act.

Some have pointed to off-bottom aquaculture as a more reliable way to produce oysters. But even its most ardent proponents acknowledge that aquaculture can produce only a fraction of natural bottom reefs can produce. Aquacultured oysters are also a lot more expensive. If we don’t start taking better care of our water, we all need to get used to paying $3.00 or more per oyster.